Welcome back for part 2 of a 3-part series that shares my story of friendship with the Pena family, a family of Adobe brickmakers in the Las Mojoneras Colonia of Puerto Vallarta, Mexico. If you missed part one, where I shared how I came to know them, take a quick look at the previous article for the backstory. I have known Ramon Pena and his family for two years. After each visit to Charro’s production yard, I come away with greater respect and admiration for him and his family. In this article, I share with you some images of those who make the bricks.

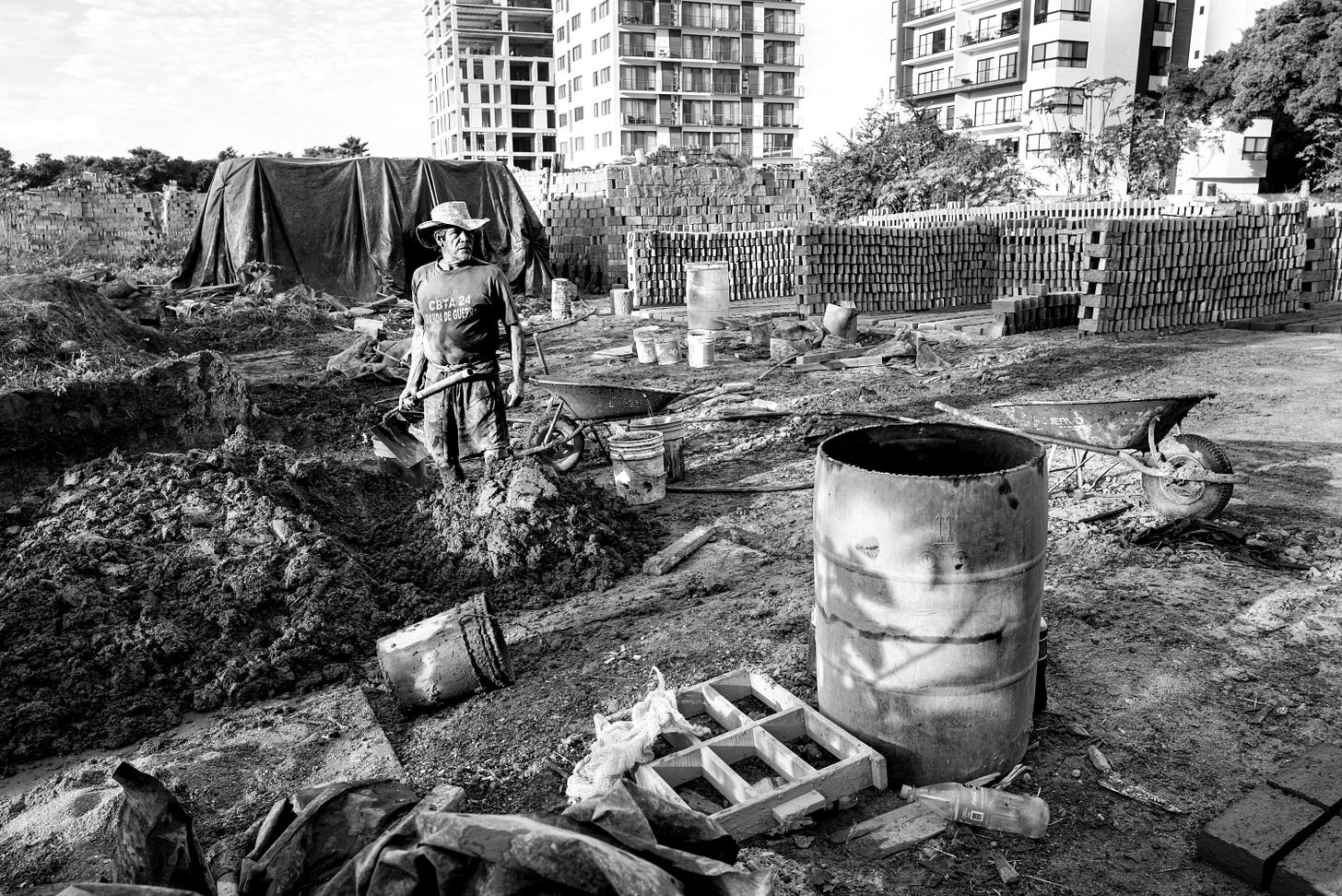

The first time I watched men (son Roberto above) of the ‘la familia Pena’ work barefoot in the soil/sawdust mix, I understood that adobe brickmaking is not just a job—it’s an unspoken conversation between the generations. With the brickmaking process passed down from his grandfather, Charro and his sons mix and shape the clay and organic mixture into bricks—each one a small part of the years of skill and perseverance in a craft that supports a wife, five children, and six grandchildren. The leased land where production takes place is rich in history. Years of remnant construction materials and cast-off family possessions lie in the shadow of the high-rise buildings. These concrete buildings stand watch over the land, ready to claim it as a part of gentrification. But for now, while he still can, Charro and his family work with the determination of a man determined to finish what he started. The land is sold, and Charro must leave.

Charro has told me stories of how, at just seven years old, his first job was to clean the sides of newly formed bricks, guaranteeing uniformity. That early discipline formed the foundation for everything he does today. Now, in his sixties, he knows how to manage the entire operation—coordinating the daily workflow, reading the weather, and working materials so precisely that nothing goes to waste. There’s no mechanization here—only hands, feet, sun, and time. Any tools used in the yard are made from salvaged wood and metal, many of which have been shaped and reshaped over the years through use.

The physicality of the work is humbling. Charro’s crew, primarily family members, move tirelessly under the Mexican sun, shifting piles of dirt, hauling water in buckets, and flipping bricks with the same reverence others might reserve for glass. Close by is a 73-year-old man who works as if age did not define his ability to work. He bends, lifts, and forms bricks in the same rhythm as men half his age. He and Charro have been friends for decades. When I asked how long he’d been making bricks, he paused, then said, “Desde siempre.” Since always.

The Peña family is the primary workforce in the operation. Charro’s sons and his eldest grandson are deeply involved, learning from him the way he once learned from his grandfather. There is something unspoken between them—an understanding that the work is more than economic survival. It is identity. In the small Colonia of Las Mojoneras, Adobe brickmaking has long been the trade that tied families to land, to rhythm, and one another. But now, as concrete and steel rise on all sides, the demand for Adobe has decreased.. Fewer architects and builders are opting for this natural, centuries-old material in their structures. The brickyard, once surrounded by similar operations, now feels like an island in the middle of an advancing enemy.

Development pressures have already made their presence felt. Charro is only permitted to fire his bricks after 4 p.m., and only on alternating Fridays, to accommodate nearby condos and a school. As with all changes, Charro has adapted. When it rains and threatens to damage the freshly formed “green” bricks, he covers everything with black plastic. When he’s delayed in cooking the bricks, he waits. He is optimistic, he is resilient, and he continues to work.

In this slow unraveling, there is no blame and no despair.. That is not how the Peña family operates. Setbacks are met with shrugs, then jokes, then laughter. When bricks crack during the drying process, they are set aside for use in footpaths or family projects at home. Nothing is discarded. Workday breaks are shared in the shade of a large stack of bricks between tasks, and any small success—a big order, a dry week, a good source of new materials—is met with the same resolve and determination to carry on.

There’s a quiet heroism in their togetherness. Even as their future is clouded with uncertainty, they are grounded in the present. They work. They adapt. They keep moving forward, one brick at a time.

As I walk through the yard, I stop and admire these craftsmen who steadily work at what might be seen as monotonous tasks. I often wonder if they think I am the strangest of characters, visiting them regularly in their yard to watch them and photograph them at work. There are no other women in any of the brickyards. The women are at home caring for the house and the children. Even though I have explained why I ask to observe their work and have provided many prints I have made for them, I suspect that they believe me to be one of those strangely independent American women who don’t always follow the rules and do what is expected of them. For now, I continue to visit and to enjoy the privilege of the Pena family friendship. Call me crazy. I call myself grateful.

Part 3 is coming up soon.

I love the statement, “Even as their future is clouded with uncertainty they are grounded in the future” Beautifully written….